In recent decades, public schools find themselves facing the greater needs of diverse student populations, with varying cognitive abilities, maturity levels, and academic strengths and weaknesses. While most typical elementary, middle, and high school students find themselves immersed in a classroom of twenty to thirty peers with one lead teacher, most public schools also have “self-contained” classrooms to provide alternative settings for enhanced academic support for the children whose needs cannot be fully met in a general education classroom.

What are Self-Contained Classrooms?

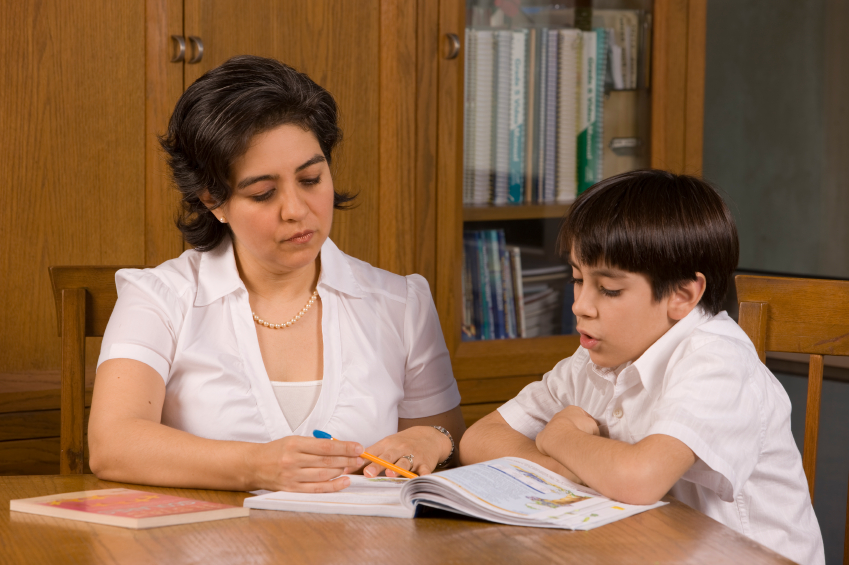

Unlike standard classrooms with a large number of peers, self-contained classrooms are typically smaller settings with a fewer number of students. Created to help foster enhanced support for students with special needs or specific difficulties, self-contained rooms are generally comprised of about ten students with unique struggles who are most commonly instructed by a lead teacher with a certification in special education. Self-contained classrooms will also have at least one paraeducator who provides instructional support under the guidance of the classroom teacher.

Due to recent curriculum shifts, some self-contained rooms cater to the diverse needs of students, such as those coping with autism spectrum disorder. A lead teacher, who is highly trained to help support students with autism, is able to provide greater assistance than what these students would typically receive in a classroom with a larger student-to-teacher ratio. Other examples of students who may be enrolled in self-contained rooms include students with developmental issues, behavioral concerns, students with specific academic struggles (i.e. in math, reading, science), or students learning to read with dyslexia.

Subsequently, due to the unique demands of all students enrolled in public schools, many educators have found that self-contained classrooms provide a more positive and supportive environment for academic, personal, and even social development. Traditionally, self-contained classrooms were intended to help students who demonstrated special needs, or to assist students who were struggling with classes or curriculum content. However, as the achievement gap among students continues to grow, many public schools question whether self-contained classrooms are the best avenue for student learning and support.

The History of Self-Contained Classrooms

While self-contained classrooms have been used in public schools for decades, these classrooms grew in popularity as the regulations of “No Child Left Behind” became increasingly severe. Essentially, the “No Child Left Behind” statute requires that all students participate in standardized tests to rate and rank a school’s performance. As this assessment procedure was nationally enforced, teachers who instructed struggling students with various cognitive challenges frequently had low test score averages, while teachers who instructed average or honors students had higher scores. Subsequently, many schools began placing a greater number of struggling students in self-contained classrooms to ensure that specific class test-score averages remained high.

The Purpose of Self-Contained Classrooms

A self-contained classroom is generally designed to provide struggling students with specialized support and interventions. For example, many students coping with autism spectrum disorder are pulled out of standard classes in order to work with special needs experts on an array of skills, lessons, and tutorials to enhance each student’s progress. In many other cases, students who are learning to read with dyslexia, students with Attention Deficit Disorder or ADHD, or students who display a general struggle in “regular” classrooms are also candidates for self-contained instruction.

In the past, students with special needs might have spent their entire day in a self-contained classroom. And while severely disabled students may still do so, for the most part, special needs kids spend at least part of their day in regular education classrooms. The level to which special needs children are integrated into regular education classrooms largely rests upon that child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP). Among other things, an IEP explicitly states what services a child will receive in school. This includes how the curriculum is delivered to the child and what aids and services the child is eligible to receive, including program modifications like self-contained classrooms.

Although self-contained classrooms provide many benefits for children with special needs, interaction with their peers is also very important. In recent years, schools have moved toward a model of mainstreaming or inclusivity. The Wisconsin Education Association Council (WEAC) defines mainstreaming as “selective placement of special education students in one or more regular education classes.” The purpose of mainstreaming is to give special needs students the peer-to-peer interaction they need, but doing so in classes that suit the child’s strengths or academic interests. For example, a child with a traumatic brain injury who particularly enjoys social studies might spend his entire day in a self-contained classroom, except for the daily period in which he joins the regular education social studies class. In this situation, the child would be accompanied by a paraeducator who would assist the child with reading, writing, note taking, test taking and other common classroom duties.

Inclusion, as defined by WEAC, is educating a child “to the maximum extent appropriate in the school and classroom he or she would otherwise attend.” In this situation, services are brought to the child with special needs, rather than the child leaving the regular education classroom. Again, paraeducators will often work with the special needs student to assist with assignments, testing and other tasks. The regular education teacher and the student’s peers will also engage with the special needs student to create an environment in which the student gleans academic knowledge and skills, as well as social and emotional skills.

Which Students Should be Placed in Self-Contained Classrooms?

While most community members and school leaders agree that self-contained classrooms provide struggling students with much needed support, many parents and school leaders are concerned about the target audience for this educational intervention.

As researchers Algozzine and Morsink explain in the journal Exceptional Children, there are specific cases of students who, without doubt, need more personal and unique interventions: “Clearly, there is a need for specially designed instruction for some exceptional students. For example, it is difficult to imagine not providing specialized classroom interventions for individuals who are blind or deaf.” While students with specific needs are provided with interventions and public school support, a new wave of educational experts argue that this approach is leaving out a significant student population—the academically gifted.

“Gifted” or “TAG” students (Talented and Gifted) often express that their standard courses of study fail to meet their own unique and special needs. While schools address the needs of those who are cognitively, behaviorally, and emotionally struggling, many public schools have not extended this support to students who desire a greater challenge.

As the University of Michigan reveals in their resource “Gifted Education,” self-contained classrooms for gifted children provide unique instruction and intervention strategies for all public school students. As many academically gifted kids often feel excluded by peers, bullied, teased, or taunted for their skills and abilities, self-contained rooms for gifted kids would allow this population of students to work with peers who are faced with the same struggles. This, as research supports, is a benefit that struggling students are able to experience in self-contained classrooms as well.

The National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) estimates that 5-7 percent of children attending U.S. public schools are academically gifted. To address the needs of these students, many schools across the nation have implemented special programs and classes. This might take the form of Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate or honors courses in public high schools. In elementary and middle schools, gifted children might be pulled out of a regular classroom for part of the day to engage in studies in a self-contained class with other gifted students. Some public school districts offer specialized gifted and talented programs that provide gifted students more rigorous classroom studies, as well as opportunities to compete in academic-related competitions such as History Day and Odyssey of the Mind.

The debate over equality in education is not one that will soon be resolved. However, mainstreaming, inclusivity and self-contained classrooms are moves in the right direction. At the end of the day, schools, parents and teachers are doing the best they can to ensure each child – special need or not – receives the best education they can in the least restrictive environment possible. If you have a child with special needs, be sure to contact his or her school and inquire about the range of services available to them to maximize their educational experience.