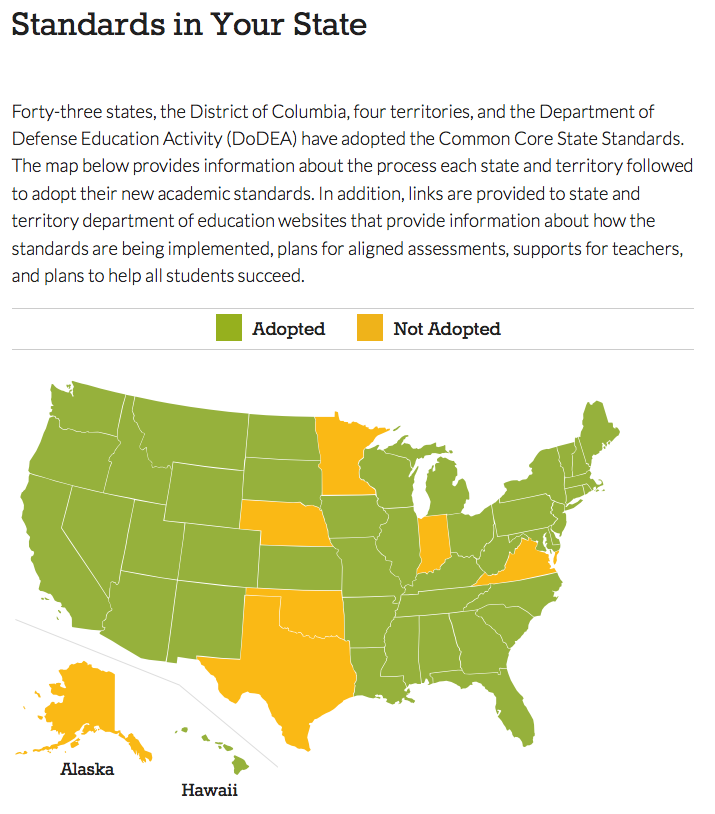

The Common Core State Standards were developed after education officials became concerned over the lack of progress American students were making in the areas of math and language arts. After years of being outperformed by children in other countries, various stakeholders came together to devise a new set of standards that would raise the bar for student learning. The result was the Common Core, which took shape over the course of 2009 and was implemented in 2010. In the years since, 43 states, Washington, D.C., the education wing of the Department of Defense, and several U.S. territories have adopted the standards.

Developed by Experts

The Common Core standards represent a cooperative effort between dozens of officials including governors, teachers, curriculum design experts, and researchers. However, two agencies, the National Governors Association for Best Practices (NGA) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) led the charge for the creation of the standards and continue to lead the ongoing efforts to implement the standards nationwide.

Throughout the design process, the NGA and CCSSO relied on input from content-area experts, teachers, and even parents to devise standards that are both rigorous and relevant to a modern-day education. The authors of the standards also worked with higher education officials, workforce trainers, and employers to ensure the standards facilitated the development of knowledge and skills required for success in college, at the workplace, and in life.

Purpose of the Standards

The standards-based movement was borne out of a desire for more commonality in the scope and sequence of topics taught in K-12 public schools. By having a set of common standards, students could receive a comparable education regardless of who their teacher was or what school they attended. In the early years of No Child Left Behind, the federal education law that requires yearly testing of children in grades three through twelve, states were responsible for developing their own sets of standards. These standards often varied wildly in their rigor as well as their content, making it impossible to compare the academic performances of children in different states. The result is that children in some states graduated from public school with far greater assets than children in other states, even if they took the same classes.

This short video explains the Common Core.

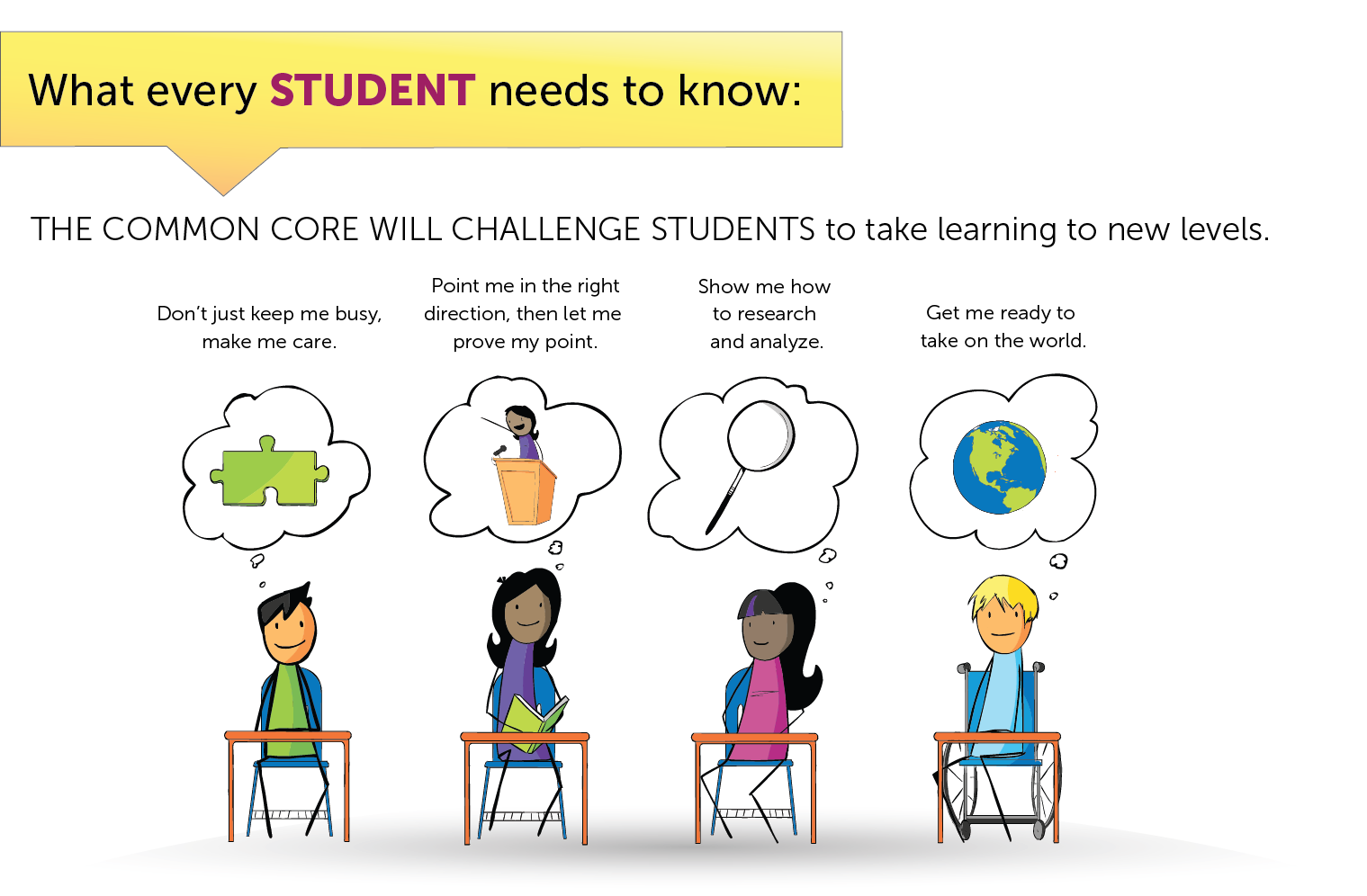

The impetus of the Common Core was to address this wide state-to-state variability. By creating a framework of essential knowledge and skills, the Common Core initiative provides more detailed guidance with regard to what children should learn and know at each grade level. With common benchmarks and definitions of proficiency, student performance in Common Core states can now be more effectively compared. And since the Common Core Standards are far more rigorous than their predecessors, their adoption means a step up for most states in terms of the depth of knowledge students are required to have.

Yet, although the standards were created to ensure that all students have the same skillset in math and English language arts, their implementation is still left to local and state officials. Additionally, the manner in which the standards are taught, the development of the curriculum around the standards, and the materials that teachers use to support teaching the standards are determined wholly by teachers, administrators, local school boards, and state education officials. Assessments to determine proficiency on the Common Core Standards will also be devised and implemented at the state and local levels. In short, the standards specify what children should learn, but how teachers deliver the content and the manner in which students are tested is left up to state and local officials.

Benefits of the Standards

In addition to providing a clear set of expectations for student learning, Common Core brings the United States in line with other industrialized nations, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, France, and Australia, that teach their children based on a single set of nationwide standards. Having this commonality also means that educational companies that used to prepare materials for over fifty different sets of standards can now focus on providing high-quality materials and programs based on the Common Core.

Image Source: Live Binders

Furthermore, the Common Core addresses the difficulty encountered by students who moved or transferred to a new school: A child coming into a new district may or may not have been prepared for that district’s curriculum. Their skillset might have been far more advanced or woefully inadequate. With Common Core, which provides subject matter sequencing from grade to grade, students that switch schools should have an easier time making that transition. State assessments will also be more comparable than in the past. Although control of assessment development remains in the hands of the states, having a common basis of knowledge and skills for student learning will bring state tests much closer together in terms of expectations and rigor. It is this increased rigor that the authors of the Common Core hope will allow U.S. students to compete more effectively against students from other nations.

Criticisms and Misgivings of the Standards

From the outset, the Common Core State Standards have faced a mountain of criticism. The majority of resistance has come from conservative groups that feel that the Common Core is tantamount to a federal takeover of education, an area of responsibility, they point out, that is squarely in the hands of the states. In fact, in 2013, the Republic National Committee adopted a resolution calling the Common Core an “overreach [by the federal government] to control the education of our children.”

Other criticisms have targeted the implementation of the standards. Earlier this year, the National Education Association (NEA), the nation’s largest teacher’s union, called for a delay in the adoption of the Common Core in order to provide more comprehensive training to teachers and administrators with regard to the demands of new standards. As it stands, the NEA complains, there is far too little quality training for the implementation of such an enormous change. While the NEA still supports the standards themselves (it should be noted as well that the NEA participated in the development of the standards) they do have reservations about the lack of preparation for the implementation of the standards.

Likely the most common sticking point for opponents of the Common Core is the erroneous belief that the federal government was in charge of creating the standards and is directing the nationwide adoption of the standards. While the Obama administration has offered incentives to states that adopt the standards, there is no federal mandate for states to do so – the process remains completely voluntary. As for the federal government’s role in the development of the standards, there was none. A consortium of education experts completely independent of any state or federal government oversight devised the standards.

Another misconception about Common Core is that they require states to test students more often and collect more data regarding their achievement. The creation of state assessments and systems for tracking students’ academic progress from third grade through to college came not from the Common Core, but from the Obama administration’s Race to the Top program. Where the confusion comes from is that Race to the Top also provided incentives to states that adopted Common Core. As a result, many states that adopted the new standards did so at a time when they were also developing new state assessments. While scores from Common Core-aligned tests are a part of states’ data collection practices, data collection is a result of Race to the Top, not Common Core.

Nevertheless, Common Core is facing increasing skepticism, particularly in states that tend to be conservative. Alaska, Virginia, Nebraska, and Texas never adopted the Common Core in the first place, and over the course of this year, an additional three states joined them after initially adopting the new standards. Indiana dropped the Common Core in March of this year, followed soon thereafter by South Carolina and Oklahoma. In each case, state officials said that the educational needs of students are best served by decision-makers at the state - not federal - level.

How Does Common Core Change Math?

The Common Core math standards essentially streamline the study of mathematics into fewer standards that are more rigorous. Rather than trying to teach every concept possible without much depth or breadth, the Common Core slims down the number of topics to focus on those that are most important to furthering one’s education and performing effectively in a job situation. The standards lay out guidelines for teaching these core concepts in a clear and coherent manner in which concepts build upon one another from grade level to grade level. The goal is that children will have a high degree of conceptual knowledge, as well as fluency with regard to procedural skills.

For example, the sequencing of the math standards calls for children in kindergarten through the second grade to study addition and subtraction. Once those concepts are mastered, children in grades three through five studies the more difficult concepts of fractions, multiplication, and division. In grades six through eight, the rigor is increased again as children tackle proportions, ratios, and algebraic concepts. By the time they reach high school, students are prepared to be successful in more advanced math classes like geometry and trigonometry.

How Does Common Core Change English?

As with the math standards, the goal of the Common Core is to zero in on the most important skills so students develop a deeper understanding and greater capacity for applying their knowledge. In particular, the Common Core’s English language arts standards represent a significant shift toward evidence-based writing and reading informational texts and nonfiction works at increasing levels of difficulty. Doing so prepares students for the complexity of reading and writing tasks they will encounter in college and at work.

For example, the standards suggest that elementary school students engage in a mixture of readings that include literature, such as short stories and poems, and nonfiction, such as content-specific texts in social studies, the arts and sciences, and career/vocational courses. This emphasis on reading across subjects is intended to develop the skills students need to be successful readers both in and out of their language arts classroom, as reading for information in history class and understanding the technical language of that subject is much different than understanding technical language in science class.

The types of questions that students are asked to answer also shift under the Common Core. Rather than engaging students in tasks that only require what they already know, the Common Core seeks to construct text-dependent skills, in which students answer questions that require inferences based on careful attention to their readings. Similarly, student writings, which have in the past been focused on the narrative genre, will shift to a more evidence-based approach, in which students are expected to develop skills for argumentative and informative compositions that are based on research.

Despite the belief by some that the Common Core English language arts standards require students to read certain texts, this is not the case. The only readings the standards specify are literary classics and foundational documents in American history, and the only author mentioned is Shakespeare. Common Core does offer a list of exemplar texts for use at each grade level, but there are merely suggestions and are in no way required to be used.

Standards vs. Curriculum

The difference between standards and a curriculum can be lost on many people outside the education sector. Whereas a curriculum is a highly detailed, longitudinal plan of learning and instruction, standards simply specify what children at each grade level should know and be able to do. In that regard, standards are just one piece of a curriculum, along with textbooks, lesson plans, assessments, and other components of teaching and learning.

For example, the Common Core Standards were developed by educational experts, policymakers, and bureaucrats to outline a long-term scope of educational goals. In math, a standard might be for a kindergarten student to be able to count to 100. A curriculum, meanwhile, is developed at the local level, oftentimes by administrators and teachers, and is much more detailed in terms of how students should achieve proficiency on a standard. In this case, the curriculum might specify that kindergarten students learn the names of each number between one and one hundred and be able to count to 100 by 1s and 10s.

Looking Ahead

The debates that have arisen with regard to Common Core highlight two issues that will continue to cause concern for American educational officials. First, the U.S. continues to lag far behind other industrialized nations in student achievement in math, science, and reading, and that gap continues to widen. Second, although both supporters and detractors of the Common Core want the same thing – the best possible education for America’s children – exactly how to ensure that happens is far from agreed upon. Whether the country continues to work on Common Core or states return to more localized control, one thing is certain: In order to keep pace with other countries, changes must be made to the U.S. educational system.

Questions? Contact us on Facebook. @publicschoolreview