It is no secret that youth of color, particularly black boys, face a mountain of obstacles to success. Black boys are more likely than their white peers to be suspended or expelled from school, more likely to drop out, less likely to graduate from high school, more likely to be unemployed, in prison, and die at an early age. These are problems that school districts, cities, and states have sought to fix for years and years, but with only pockets of success. It is a bleak outlook, but one that the Obama administration seeks to change with the most comprehensive reform and aid effort yet.

About the Initiative

The overarching purpose of My Brother’s Keeper is to address gaps in educational and related services that persist for young men of color. The initiative is a cooperation between local, state, and federal agencies, private business, and non-profits to bring essential services to the nation’s neediest youth. In total, the initiative includes five primary goals:

- Prepare Children to Learn – Provide support programs that foster intellectual, physical, social, and emotional growth so children are prepared to begin school.

- Boost Literacy – Support early learning initiatives that get children reading at grade level by age 8.

- Help Kids Graduate from High School Prepared for College – Promote educational programs that prepare students for success in postsecondary environments and facilitate training for in-demand jobs.

- Facilitate Workforce Readiness – Assist youth in finding quality jobs that allow them to support themselves and their families.

- Keep Children on Track and Give Them Second Chances - Protect children from violent crime and for those that have been incarcerated, provide them with education, training, and treatment that will allow them to have a second chance at a good life.

Young men of color face larger obstacles to success than African-American and Latino girls, which is why My Brother’s Keeper focuses on providing educational and social supports from early childhood into young adulthood for young men. These programs aim to keep boys on a positive life track and seek to combat the school-to-prison pipeline that removes so many minority boys from society and mires them in a lifetime of prison sentences.

Thus far, the initiative has garnered hundreds of millions of dollars of support from philanthropic organizations, major corporations, and even professional sports. The NBA has committed to recruiting 25,000 men of color to serve as mentors. The Citi Foundation is on board to provide $10 million to devise college readiness programs for minority youth. Another $18 million has been donated by AT&T to fund services that target children at risk of dropping out of school.

The initiative is heavily focused on research-based methods to make improvements at the local level. While initially the program will rely on federal student outcomes data, the White House has convened a task force to help local officials collect and analyze their own data to devise strategies for improving the achievement of minority boys. Using that localized data, schools can then adopt critical success indicators that are most applicable to their population of boys of color.

In May of this year, the initiative’s task force made it’s first round of recommendations, which include launching a nationwide campaign to recruit quality mentors for minority boys, promoting literacy and reading among minority families, providing summer learning opportunities and apprenticeships, and eliminating suspensions and expulsions as discipline options for preschoolers. Additionally, the task force will:

- Identify areas of need in order to develop programs that eliminate negative outcomes.

- Create an online catalogue of strategies that prove successful in providing opportunities and improving outcomes for boys of color. This catalogue will be accessible to all stakeholders.

- Devise a public website that will disseminate information about the efficacy of programs implemented at schools across the nation.

- Continue efforts to build a coalition that will support My Brother’s Keeper for the long-term.

Large Public School Involvement

My Brother’s Keeper was joined in July by 60 of the nation’s largest school districts, which together comprise roughly 40 percent of all Hispanic and African-American boys that live in poverty. Each district has committed to expanding access to preschool programs, improving data tracking to identify academic struggles early on, and increase the number of minority boys involved in Advanced Placement courses and gifted programs. Additionally, all 60 districts have pledged to change disciplinary policies that disproportionately target boys of color and implement strategies to increase graduation rates, particularly among Hispanic and African-American young men, although supportive services are also being devised for Native American and Asian American boys as well.

The Metro Nashville Public Schools have joined My Brother’s Keeper, which in that district will focus on expanding pre-k offerings, devising early warning systems to reduce grade retentions, and providing support for minority boys who seek to attend college. The initiative will coincide with a district program to address discipline gaps for minority students. That program, entitled Positive and Safe Schools Advancing Greater Equity (PASSAGE), will examine the internal policies and practices of the district that unfairly target students of color.

In the Kansas City Public Schools, the emphasis will be on wraparound social services intended to keep young black men in school and on track to graduate. Included in these wraparound programs are improved access to quality preschool services, expanded before and after-school programs, initiatives to reduce absences from school, and improved monitoring of students’ academic progress so interventions can be made early on if problems are identified. An effort to encourage black male students to apply to college, fill out and submit financial aid documents, and take higher-level courses in high school will also be made.

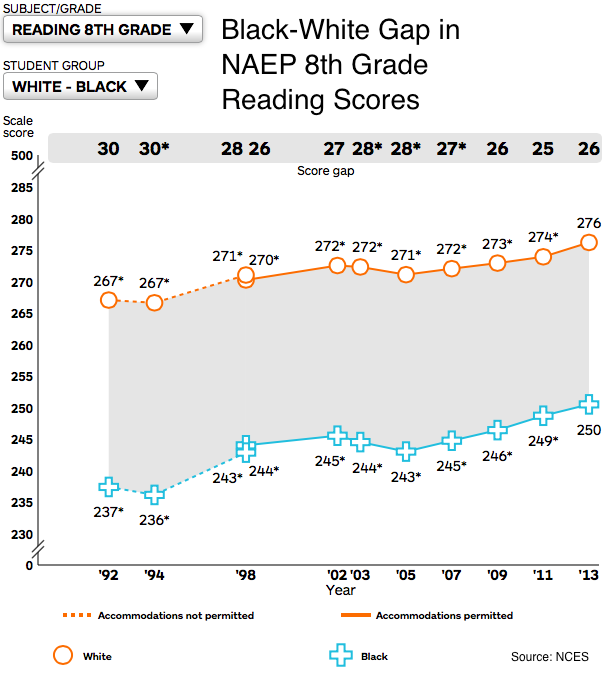

My Brother’s Keeper will be implemented in Milwaukee Public Schools as well, where for decades African-American male students have faced higher suspension rates, lower scores on measures of reading and math, and higher high school drop out rates than their peers. In fact, Wisconsin ranks as the state with the greatest racial disparity in achievement. While overall the state ranks in the top third in terms of math scores on the National Assessment of Education Progress, African-American boys ranked fourth worst. Reading scores on the were even worse, with Wisconsin’s black young men scoring dead last on the eighth grade test and second to last on the fourth grade test. This achievement gap, according to Senator Luther Olsen, is both “embarrassing” and “ridiculous.”

What’s Happened Thus Far

One of the first tasks the Obama administration undertook as part of My Brother’s Keeper was to examine data regarding employment, poverty, and violence among minority male populations. The results were disheartening:

- During the summer of 2013, just 17 percent of black boys and 28 percent of Hispanic boys between the ages of 16 and 19 were employed.

- Over 23 percent of Hispanics, nearly 26 percent of blacks, and 27 percent of Native Americans live in poverty, compared to less than 12 percent of whites.

- Black males accounted for 43 percent of murder victims in 2011, even though they comprise less than six percent of the overall population.

Yet, given the plight that many young minority men have faced for decades, these statistics are not all that surprising. What is important is that the White House task force is using this data to drive the creation of short and long-term programs to address these issues, such as high quality early childhood education, cradle-to-college strategies, and reform of the juvenile and criminal justice systems. Now that the nation’s largest school districts are on board with the program, they will be able to implement programming that targets the specific needs of their communities.

In these first six months of My Brother’s Keeper, the effort to build a coalition of public and private sector stakeholders has gone very well. In addition to the organizations mentioned above that have pledged millions of dollars to the effort, Americorps and the U.S. Forest Service have created the 21st Century Conservation Service Corps. Nearly $4 million has been pledged between the two organizations to get the program started, which will provide minority boys with forest restoration skills and opportunities for careers in the Department of Agriculture. Americorps is also working with the United States Department of Justice to create the Youth Opportunity Americorps. The essential function of this program is to bring youth that are disengaged and disenfranchised into service programs to provide them with job skills training and work experience that can parlay into future careers.

Another highlight in the early going is the efforts by the Emerson Collective to support the creation of innovative high schools to meet the demands of the 21st century economy. The Emerson Collective, in partnership with local school districts, will launch a competition to improve school environments such that they are engaging, inventive, and prepare students for future economic demands. The program is being funded to the tune of $50 million by the Emerson Collective and it’s partners in the technology sector.

Discovery Communications has also joined My Brother’s Keeper with a pledge of more than $1 million to support public education efforts related to the negative perceptions of minority youth. Discovery will highlight how specific interventions make a positive impact on youth of color and host town-hall style meetings to highlight ways that communities can implement similar programs to help lift up minority youth in their area.

Criticisms of the Program

The fact that My Brother’s Keeper is focused solely on boys has been a primary sticking point for advocates of girls and young women of color who face gaps in services and opportunities that are not far behind those of boys. Other critics wonder how a program intent on providing a hand up to all the nation’s minority boys can possibly achieve it’s goals when, although funded with hundreds of millions of dollars, has a comparatively meager budget for the breadth and depth of services proposed.

The fate of the program once President Obama leaves office is, for some, a major concern as well. Many wonder how well the program will be funded in the future, or if it will even survive once a new administration takes over. Detractors also argue that My Brother’s Keeper is a far too conservative measure to address the issues surrounding race and opportunity. By focusing mostly on education, critics maintain that the initiative largely ignores the underlying forces that serve to subjugate minorities, primarily persistent institutional racism that pervades education, the workforce, and the criminal justice system.

However, supporters of My Brother’s Keeper are quick to point out that this initiative is not dependent upon any one administration because it receives no funding from the federal government. The coalition of private organizations should allow the initiative continued growth regardless of who is in the Oval Office. Furthermore, supporters argue that My Brother’s Keeper doesn’t seek to exclude any groups in need, but rather focuses on the one group that faces the most robust socioeconomic obstacles to success, primarily poverty, crime, and incarceration. According to Cedric Brown, managing partner of the Kapor Center for Social Impact, “this situation has grown so dire, particularly around violence,” that these programs for minority boys cannot wait. While the framework of My Brother’s Keeper may not be ideal and may not address the bigotry and prejudice many minorities encounter on a daily basis, it is, nevertheless, positive progress on an issue of immediate national importance.

And of national importance it is. Black boys lag behind their peers in nearly every academic indicator in nearly every municipality in every state in the nation. It is not a problem of the Deep South, nor a problem facing only urban districts. Wherever boys of color attend school, they do not perform at a level on par with their peers, and that needs to change. Yet it isn’t just a school-based issue. Young minority boys need improved access to health care, nutrition, and employment services. Their neighborhoods need to be safer, their fathers more involved in their lives, and their communities more accepting of them. These are all issues that have persisted for generations and ones that many intervention efforts have sought to address. My Brother’s Keeper may be the best hope yet that change will finally come.