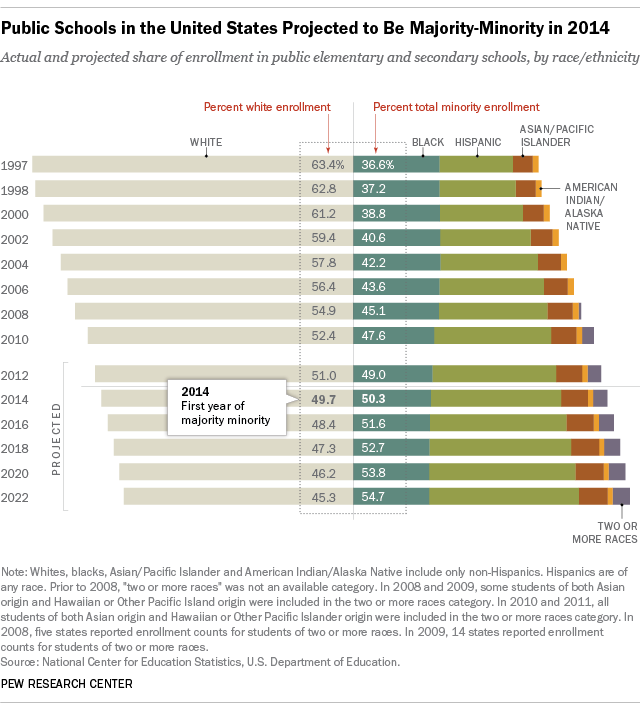

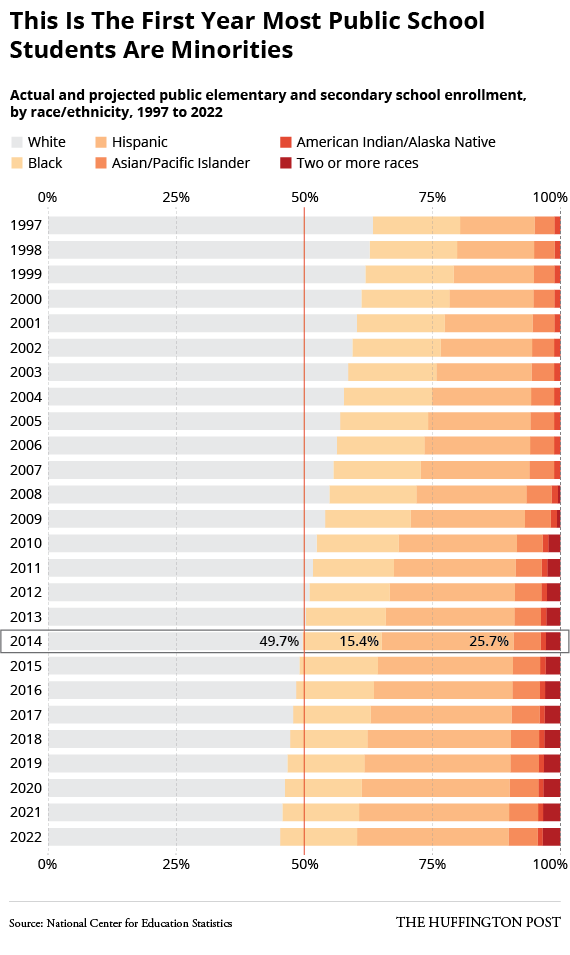

It has been an ongoing trend for nearly two decades – while the total number of students in American public schools has risen, the percentage of those students who are white has steadily fallen. According to the Pew Research Center, in 1997, over 63 percent of the 46.1 million U.S. public school students were white. Today, white students comprise just 49.7 percent of the 50 million students enrolled.

These changes in the racial makeup of the nation’s public schools reflect where the overall population is headed. According to recent estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, by 2060, the white population in this country is projected to fall by more than 20 million people, while the Hispanic population is set to double. Black and Asian populations are expected to increase as well, although at rates far slower than Hispanics. By 2043, the nation as a whole is projected to become majority-minority.

Public School Diversity

While the white student population has declined by 15 percent since 1997, according to Pew, both Hispanic and Asian populations have rapidly increased. In that same time frame, Hispanic students have grown by 50 percent to 12.9 million. The number of Asian students has also seen significant growth, jumping 46 percent to 2.9 million students. The African-American student population, which will number 7.7 million this fall, has remained relatively steady over the last twenty years.

Much has been made recently of the number of migrant children entering the country and enrolling in public schools. Still, it is actually U.S.-born children of immigrants that account for the explosive growth of the minority student population. The Pew Research Center notes that between 1997 and 2013, the number of U.S.-born Asians increased by 50 percent, while the number of Asian immigrants during that time grew by just 9 percent. Among U.S.-born Hispanics, the number of children between the ages of 5 and 17 jumped by a whopping 98 percent between 1997 and 2013, while immigrant children of the same age actually declined by more than one quarter over the same time period.

Over half of students in pre-K through the eighth grade are from a minority group, while 48 percent of high school-aged students are minorities. However, the impact of increased minority enrollment is most salient at the elementary school level. Hispanic children alone account for a large portion of minority students, comprising at least 20 percent of kindergarten classes in 17 states, up from just eight states a little more than a decade ago. This growth is seen in states with large Hispanic populations, such as California and Florida. But Hispanics now account for more than 20 percent of kindergartners in states like Idaho and Massachusetts, which have relatively low overall Hispanic populations. What’s more, in some states, including Oregon and Kansas, Hispanic children account for more than one-quarter of all kindergarten students. The ethnic and cultural shift of American public schools is occurring in every corner of the nation, in both rural and urban districts large and small.

Increased Need for English Language Learner Classes

The rapidly increasing number of children whose native language is not English necessitates the development of more robust English language learner courses, particularly at the elementary school level. According to the Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, nearly one-quarter of all children in the United States have a foreign-born parent. As a result, more than one-fourth of American children are now bilingual. However, because many children who are immigrants or whose parents are immigrants speak a language other than English at home, a full 70 percent will require some level of English language instruction in school. Those programs require a lot of funding for qualified teachers, extra courses after school and during summer breaks, and teaching materials.

Interestingly, while many Americans might assume that the greatest need for English-language learning courses is among Spanish-speaking populations, it is actually Asian students who will need the most instruction. Although Hispanic children far outnumber Asian children in American public schools, a greater number of Hispanic children are U.S.-born and have at least some English-speaking abilities. By contrast, the majority of growth among the U.S. Asian population is due to immigration, so children from the East arrive in U.S. public schools with little or no English language skills. Some school districts, particularly those in rural areas, have encountered difficulty finding qualified personnel who speak Asian languages.

Factors Negatively Impacting Minority Student Achievement

According to a report by The Atlantic, public schools will see 33 percent more Hispanic students, 44 percent more multi-racial students, and 2 percent more African-American students by the 2022-2023 school year. While this increased diversity presents many opportunities for positive growth, including increased social awareness and cultural understanding, it also presents some problems for public schools and children of color. Minority children, particularly those in the African-American and Hispanic communities, face a disproportionate lack of good schools and safe communities. More frequent incidents of violence, increased poverty, lack of access to healthcare, and substandard housing are just a few of the obstacles children of color typically encounter.

All these factors negatively impact the ability of minority children to learn and thus require public schools to change their approach to help children of color gain ground. According to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, among the most popular solutions to boosting minority student achievement are:

- Promote early education for all students. Just 56 percent of American Indian children aged 3-5 are currently in preschool, while an even smaller percentage of Hispanic children in the same age group attend school.

- Expand literacy programs in elementary schools. Only 17 percent of African-American fourth graders and 19 percent of Hispanic fourth graders score proficiently in reading.

- Devise programs to keep minority children in school and on track to graduate. Nationally, just 78 percent of students graduate from high school on time. But the situation is far worse for minorities: Just 66 percent of African-American students and 69 percent of American Indian students graduate with their class.

- Schools must account for social factors that are out of their control. Minority students are less likely to live in a household with two parents, are more likely to have parents who did not complete high school, and are more likely to live in poverty-stricken neighborhoods in which at least 20 percent of the community is at or below the federal poverty line. Minority children are also more likely to attend schools with fewer resources, attend classes with less rigorous curricula, and have less experienced teachers.

Teacher Diversity Remains Woefully Stagnant

Although the nation’s schoolchildren are becoming more diverse, the nation’s teaching corps is not. Of the 3.3 million teachers in the U.S. public school system in 2011, 84 percent were white. This represents little change since 1986, when 91 percent of teachers were white. In fact, over the last three years, the gap between student diversity and teacher diversity has grown by three percent. There is not a single state in the nation with a teacher population that is as diverse as its students, and in some states, the gap is enormous. For instance, in California, only 29 percent of teachers are nonwhite, while nearly three-quarters of students belong to a minority group. Although the level of interest and care a teacher displays for a student is a more important factor in student success than the teacher’s race, it certainly wouldn’t hurt to have more Hispanic, American Indian and African-American teachers standing in the front of America’s classrooms.

Embracing Change

Some schools and families have struggled mightily in accommodating the vast and quick changes that have been seen over the last few years. Racial tensions at one Chicago-area school led to a lunchroom brawl that had to be broken up by local police. Some white parents, upon seeing the diversity in their child’s southeastern Pennsylvania classroom, elected to remove their children and send them to private schools in Delaware instead. These are but two examples of the effects that poverty, inequity, and prejudice have on children who should be learning their ABCs rather than dealing with ignorance and, at times, violence at school.

As the nation’s public schools become increasingly diverse, teachers and other school personnel will be considered the flag-bearers of change. From advocating for improved early childhood education to increasing the rigor and relevance of the curriculum to fostering understanding of cultural and social mores amongst disparate groups of students, schools will be at the forefront of addressing the heavy-duty issues that the greater population faces as we continue to change in terms of how we look, the languages we speak, and the traditions we celebrate.

Questions? Contact us on Facebook. @publicschoolreview